How do libraries vanish?

Surviving obscurity as an early medieval manuscript

This is part of an ongoing series in which I delve into some of the major issues I’ll be exploring in my thesis, which focuses on the wear and damage that manifested on the pages of early medieval manuscripts. You can read my previous post in the series by clicking the link below:

"Unleash tongues with the fingers"

Have you ever dreamed of exploring a medieval library? I know I certainly have. Many historians and palaeographers would dream to know exactly what texts certain historical authors would have had access to, and study how their worldviews shifted according to the books they surrounded themselves with...

Recently, I’ve been reflecting on the sheer scale of what is lost to time as a historian. Any early medieval historian, regardless of what they might specifically study, will have encountered the issues of a lack of source material in some format. It is one of the first limitations of the study that we address, often via lengthy acknowledgements at the beginning of book chapters, articles and monographs about our (sometimes paltry) surviving corpus of evidence compared to what we know existed, but will likely never be able to access.

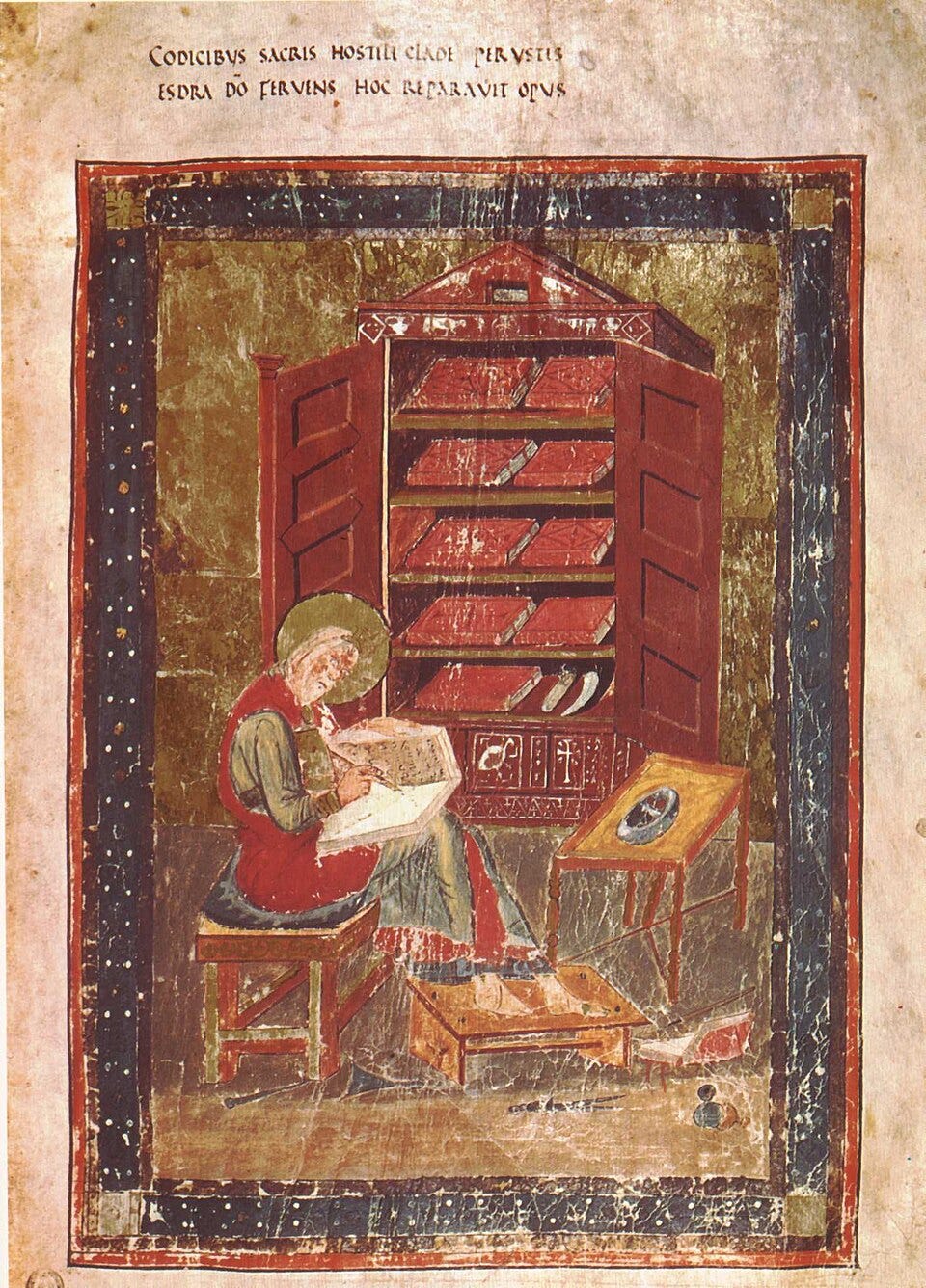

When studying the book culture of the early medieval Insular world, the decimation of the source material over the course of more than a milennia is vital background understanding for interpreting any work produced in the field, and even what we do have can sometimes be more than a little misleading once its contemporary context is considered. For example, one of the very few contemporary images that we have from the early medieval period that depicts a scholar using a library is the portrait of Ezra, from the notorious Codex Amiatinus. Made at the scriptorium of Wearmouth-Jarrow, it is considered the best preserved codex that preserves the Vulgate text of the Bible and was transported to Europe as a gift for Pope Gregory II. Thanks to the death of Ceolfrith en route to Rome, who had been accompanying the codex, the book never made it to its intended recipient.

The image displays what is known as an armarium, a cupboard specifically designed to store books, however, it has been argued by Michael Lapidge that this image cannot be representative of how the Anglo-Saxons stored their tomes. If Lapidge’s estimates are correct, and that each library in the Insular world held (approximately) 60 manuscripts in total, then it would be much more likely that these libraries would have stored their manuscripts in book chests instead, and that this image is potentially based off a continential, possibly Italian, exemplar that scribes and painters at Wearmouth-Jarrow were working from.1 Images like these, whilst contemporary, may not demonstrate an accurate portrayal of Anglo-Saxon book culture.

So, what did an early medieval library look like? We know that the older the book, the more likely it is to have suffered irreperable damage, or complete loss, meaning that many early medieval texts that would have made up the libraries of scholars such as Bede have vanished from history.2 Lapidge’s The Anglo-Saxon Library attempts to reconstruct the early medieval library, by using book lists and citations written in other books that have survived the ages, to create lists of books that authors at specific centres would have been aware of and would likely have had access to in order to support the creation of their work. However, Lapidge does not consider liturgical books (that is, books directly associated with church usage) as part of the early medieval library, which eliminates a huge amount of his potential evidence, a decision which I find short-sighted.3

It is not unreasonable to assume that, especially in smaller institutions, liturgical books may likely have been stored in the same places that non-liturgical books would have been kept. Book lists of the period also indicate that the compilers did not distinguish between liturgical and non-liturgical books when compiling their lists owned by a particular library. (This is without even going into detail over the question of where a liturgical versus a non-liturgical book can even be defined, or questioning the assumption Lapidge makes that “every church” could be expected to have owned the same ones).

Even accounting for his dismissal of liturgical books, Lapidge’s work makes it abundantly clear just how much material we have lost from these early libraries, and just how few we can identify as having belonged to a specific institution. For example, we know of a paltry few books that were, definitively, either owned by the library or produced at the scriptorium in Wearmouth-Jarrow. This is primarily since, in many cases, palaeographic evidence may be able to match just a few books to an assigned site of production since a reliable known exemplar is required for others to follow.4 This is made even more challenging by the fact that there are so few cases of an of an early medieval text block surviving in its original binding.5 It may not be that the library at Jarrow has “vanished”, but that we are not reliably able to assign a book to Jarrow at present, but it is possible that advances in bioarchaeology of parchment may be able to start to rewrite some of these lost narratives.6 How then, were so many of these books lost?

It is not always recognised that many books from the early medieval period were not lost, but were destroyed intentionally. Many older manuscripts, especially liturgical books, which were either out of fashion or out of date, would have been subject to decommissioning and recycling into new books; indeed, entire economies in the middle ages existed to facilitate the destruction and recycling of old books into the new.7 The older texts would be turned into pastedowns or binding strips that were used to increase the strength of the new book, and so their words became inadvertently preserved, only to be discovered later by archivists and conservators. Occasionally, this might be the only way in which certain texts survive, for example, in certain cases of Icelandic liturgical fragments.

There are of course many other means by which books have vanished throughout the centuries, often as a result of large, systematic changes that impacted the ways in which the church, the primary producer of manuscripts, operated. It is well known that a huge number of manuscripts in England were lost due to the sweeping religious changes made during the Reformation; books deemed “too Catholic” would likely be one of the targets of those subject to destruction, especially liturgical books. However, contemporary antiquarians and collectors were aware of the scale and importance of many of the books held at the great libraries and institutions of monasticism and set about saving them from their doom.

One such collector was Matthew Parker, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1559-1575. Parker was however, in the context of his fervert Protestantism, determined to demonstrate that the church in England had always been independent from the church in Rome, and this became his driving motivation for collection of historical manuscripts.

The collection that Parker compiled included the likes of the St Augustine Gospels, a near priceless artefact believed to have been brought by St Augustine on his mission to evangelise to Æthelberht of Kent in 597, a copy of Bede’s Historia Ecclesiastica and Version A of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Essentially, very, very important books that provide critical cornerstones of the field of early medieval research. Despite Parker’s motivations skewing the types of material that he was able to save (and his adaptations to some of the texts that he collected), without him, the field of early medieval history would be on significantly weaker grounding than it currently is today. His collection of manuscripts eventually became the Parker library, bequeathed to and housed at his former college, Corpus Christi, Cambridge.8

Even manuscripts saved from destruction have suffered losses in other ways. Parker, and other antiquarians from the early modern period right into the twentieth century, often liked to rebind their manuscripts to achieve a consistent aesthetic on their shelves. However, this would result in the loss of the original bindings, as these were discarded or recycled when the rebinding was complete, and potentially the manuscript’s original pastedowns or endleaves. In many cases, the impressions of manuscripts that we view in reading rooms today might heavily skewed by the aesthetic choices of these early modern antiquarians, which we as historians would do well to remember.

There has been immense progress made between the Reformation and today when it comes to conservation and professionalisation of archival systems, but it should be remembered that books are still intensely vulnerable objects in heritage collections. From flooding to fires (including the famous Cotton fire that destroyed a huge number of priceless early medieval manuscripts), there are many ways in which books can be lost or damaged, even if their importance has been consistently recognised throughout the ages.

The need for standardised conservation procedures were made evident during the flooding of the River Arno in 1966, causing a huge amount of damage to the city of Florence. This included many museums’ artworks (including the Uffizi), rare book and antique dealers, churches and cathedrals, the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Firenze, and many, many more.9 Whilst there was an immense outpouring of support for the city from libraries, museums and archives throughout the world, during the aftermath, it was clear that the processes of disaster conservation needed to be reorganised and streamlined, leading to the creation of a nine-step procedure in order to treat water, oil and mud damaged books.10

As a result of the Florence floods, there was a drastic advancement in the professionalisation of preservation and conservation as disciplines, designed to both forsee and mitigate future potential disasters. Whilst there had been an increasing understanding of the importance of documenting conservation and preservation practices from the 19th century, it was only after the Florence floods that documentation became far more standardised.11 Understanding previous treatment that a book might have gone through is difficult unless it has accompanying documentation, and conservation work that might have been undertaken by a manuscript’s owners prior to the 1960s was likely not recorded.

Treatments and conservation work can vary greatly depending on an institution’s goals and objectives, and in the case of the MacClean Collection held by the Fitzwilliam Museum, the owners’ objectives appeared to be to ensure that a manuscript was presented in the most grandiose way possible, and “restore” the textblock to its original state of presentation.12 This resulted in the manuscript being vigorously scrubbed of any dirt, likely bleached, and then rebound with custom covers. Whether or not it is a conservator’s job to restore or maintain an item is a decision that is dependent on the goals of the stakeholders at play, but most often the money and resources available to an institution. Intervention is nearly always kept to a minimum in order to preserve an item from outside harm, and occasionally, from itself, if it has been rebound in acidic bindings that can cause deterioration. In some cases, however, intervention is critical, especially in cases where the object is at risk after coming into contact with biohazards.

Before starting my PhD project, I had no idea that there were so many different kinds of mould that could infect a book. Mould can be a serious problem for conservation teams, both in terms of treating it now, but also dealing with previous conservators’ treatments if they might have damaged the book in any way, but regardless, removal of potential viable conidia is critical if a book is to be preserved.13 Upon my viewing of the Trinity Gospels at the Wren Library at Trinity College, I was warned that the page had been scrubbed viciously, the pages may have even been bleached, due to the damage that the manuscript had suffered due to mould, or potentially to remove dirt and grime deposited by previous users. It’s clearer on some pages more than others, but it’s quite evident upon viewing (and touching) that the book has been cleaned hard, though ghostly spore marks still remain on the page.

Given the number of ways and means that we can and do lose books, it seems almost a miracle that any have survived the ages to tell their tales at all. It is certainly a wonder to behold a tenth century gospel book when you hold it with your own hands, irrespective of the fact that the binding might be a nineteenth century vanity project.

Yet, even with the professionalisation of the discipline of conservation however, heritage collections are still under significant threat today. One of the major concerns added to lists of potential damage to heritage collections in previous decades is that of neglect, caused by the lack of cultivation and maintenance of collections and the nurturing or preservation of industry knowledge, often due to a lack of funding available to heritage institutions.14 UK readers will no doubt be familiar with the fact that funding available to archives and museums has been drastically reduced since the austerity programmes introduced by various Conservative led governments, alongside a general decimation in funding for arts and humanities programmes more widely.

Museums and galleries are having to do much more with less, in terms of staff, preservation and conservation, money, and outreach programmes, meaning that, for many, the ability to engage and think critically about our heritage and history will become more and more distant, trending more and more elite. The fragility of these texts, both in terms of their physical states and the reduction of accesses to them, is a stark warning to us to invest in our heritage industries, lest we allow these miraculous survivals to fade into obscurity once more.

Thank you for reading M.R. James Appreciation Society! I’m Olive and I’m a PhD student of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic at the University of Cambridge.

My research focuses on early-medieval spirituality in Britain, its manuscripts and language, the history of the book, and how texts interacted with constructed sacred space. If you’re interested in learning more about this wonderful period of history and following my postgraduate research journey, I’d be delighted to welcome you here.

All of my posts are available to read for free, but if you would like to support my work as a researcher, I have turned paid subscriptions on - they start at £3.50 per month.

If you would prefer to support me in a one-off capacity instead of committing to a full subscription, you can tip me the cost of a herbal tea (in lieu of buying me a coffee). Any and all support of my work is appreciated so much.

Lapidge, M. The Anglo-Saxon Library. (Oxford, 2006). p. 61.

Lévêque, E. “Manuscripts in the pre-printing era”. in Bainbridge, A. (eds). Conservation of books. (Oxford, 2023). p. 177.

Lapidge, M. The Anglo-Saxon Library. (Oxford, 2006). pp. 32-53

Lapidge, M. The Anglo-Saxon Library. (Oxford, 2006). p. 65

Ker, N. “The migration of manuscripts from the English libraries.” The Library, Volume s4-XXIII, Issue 1. (June 1942). p. 3.

For more information, see the Leverhulme supported project headed by Joanna Story at Leicester: “Insular Manuscripts AD 650–850: Networks of Knowledge”.

Ryley, H. Re-using manuscripts in late medieval England: repairing, recycling, sharing. (Boydell & Brewer; 2022). p. 63.

The Parker Library has digitised all of their early medieval manuscripts in a groundbreaking project known as “Parker on the Web” - available to all to explore online. A good overview of Parker’s legacy to the college can be found here.

Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi. “The 1966 flood’s damages to the art heritage of Florence”. Accessible here.

Liddel, C. “Before the flood, after the flood”. Craig Preservation Lab, Indiana University Bloomington. (April 5th, 2019). Accessible here.

F. Durant. “Introduction to preventative conservation.” in Bainbridge, A. (eds). Conservation of books. (Oxford, 2023). p. 488.

Reynolds, S. Personal communication on 11th December 2025.

Florian, M. E. Fungal facts: solving fungal problems in heritage collections. (London, 2002). p. 63.

Bendix, C. and Eng Moore, T. “The ten agents of deterioration”. in Bainbridge, A. (eds). Conservation of books. (Oxford, 2023). p. 382.

I have read this a couple of times, with great interest, thanks. Love your take on the subject which piqued my interest a couple of years back with Pliny the Younger’s Letters. When you talk about destructive processes, it poses the question ‘what other uses might medieval parchment have served?’ In the case of the Letters, annotations on the pages might suggest it was held as an adjunct to a sermon. Today we dispose of pages with little thought - gifting them to a church bazaar, or repurposing them of the floor of a budgerigar cage, or substituting them for kindling when lighting a fire (not me, it goes without saying). Could, instead, they have been sought deliberately and systematically as a useful crafting accessory - binding on a bow or tool, plastering on a wall or ceiling, bolstering the strength of a basket, chest or box. While fragile, the remaining calf skin can’t all have been collected by monks looking to recycle. Is this one of those cases where the 5th-6th century ‘silence’ tells us something else? :)

I loved how this took such a tangible image — libraries disappearing — and used it to talk about what we lose when we stop caring for memory, attention, and physical culture.