"Unleash tongues with the fingers"

How did early medieval readers interact with their books?

This is the first in a series of posts I’ll be making on early medieval reading practices, where I gradually introduce the topics and themes of my PhD research. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I enjoy writing them!

Have you ever dreamed of exploring a medieval library? I know I certainly have. Many historians and palaeographers would dream to know exactly what texts certain historical authors would have had access to, and study how their worldviews shifted according to the books they surrounded themselves with. Which specific parts of the vetus Latina were circulating in Rome when Gregory the Great composed his writings? What information did Bede have at his disposal in his library at Wearmouth-Jarrow, and what did he choose to gloss over when writing his Ecclesiastical History?

The medieval relationship with books, and indeed, the written word in general, was both similar and quite different to the way we view our books today. Whilst there are many examples of avid book collectors and enthusiasts known from the medieval period (Francis of Assisi famously collected scraps of parchment that had been written on as he believed in their intrinsic importance and sanctity of words) just as there are today, the context in which these books existed, and the way they were interacted with by their readers, was, in many cases, far more intense than a modern bibliophile.

We don’t think much of our ability to read nowadays; it is a cornerstone of educational development that is foundational to continued learning. If you can’t read, you will struggle greatly to interact with the world around you. It is sometimes hard to remember that the notion of having a population that is mostly literate is a relatively modern phenomenon; attendance at school between the ages of 5 and 10 years old was only made mandatory in 1880 in the UK, and it took until 1917 for school attendance to be mandatory throughout the entirety of the United States.

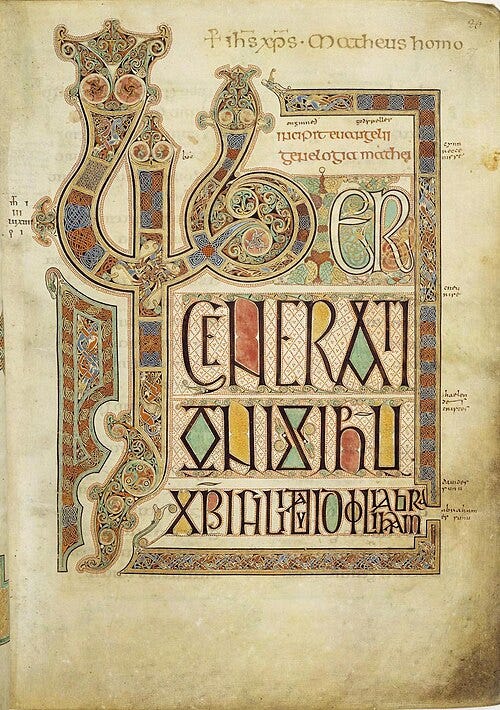

However, in the medieval period, the vast majority of people would have been illiterate, especially in the early medieval period. Literacy, especially scholarly literacy, was restricted to the ecclesiastical sphere and some educated laymen (usually royals or very high nobility). This did not mean that the book was not an object of importance for the rest of the population though; highly decorated Gospel books would serve as objects of devotion and beauty, to be admired on the lectern, a place to swear oaths and allegiances, carried in religious processions.1 For many of us, it is clear that we simply don’t view books (as material objects, at least) with the same reverence and sanctity that the medieval world did.

What caused this reverence, and why was the written word treated with such veneration in comparison to the readers of today? Whilst we have lost a huge number of books that would have existed in the early medieval period, there were simply far fewer books in circulation in the medieval period than there are today. Thanks to advancements made during the Industrial Revolution, the majority of the books that we surround ourselves with in the modern day are mass produced; we are removed entirely from their production processes, but the creation of a medieval book took much more time and effort.

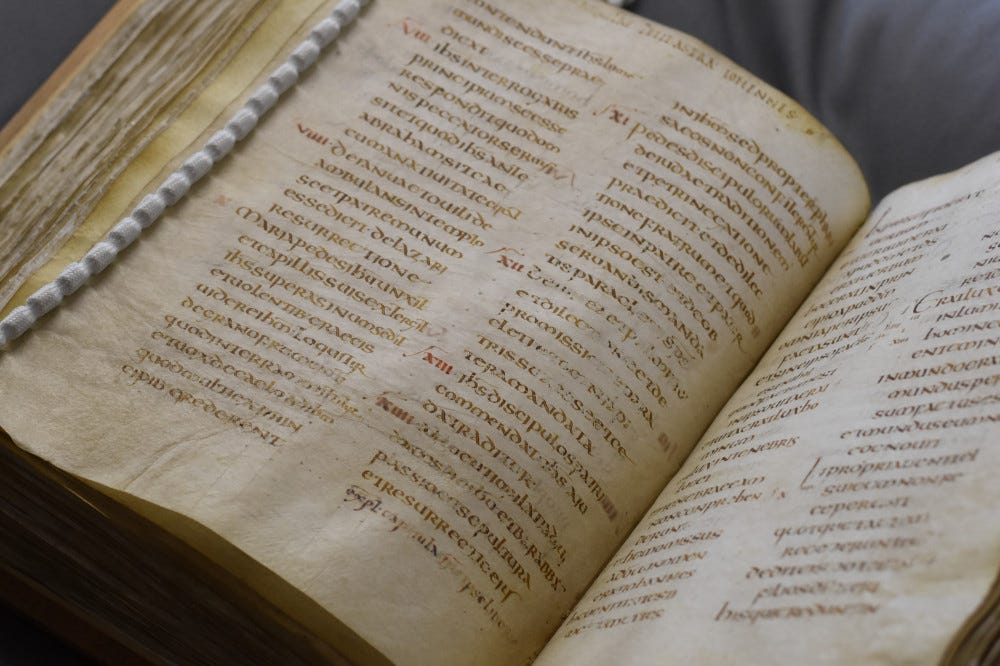

Before the dawn of the printing press and indistrialisation of book making, the creation of a single codex was prohibitively expensive for the majority of the population, so most books would have been owned by ecclesiastical centres or rich laymen, such as kings or possibly very high ranking nobility. The majority of books would have been written on parchment (animal skins), by hand (from which we get the word ‘manuscript’, from the Latin manus, hand). The production of a single book required several animals to be slaughtered and skinned. The hair was then scarefully scraped away, along with any remaining muscle tissue.

These skins would then be treated chemically, stretched taught and hung out to be dried, before being cut into sheets that could be made into folios, upon which writing could finally begin. Ink production was its own beast which could require the import of rare gemstones on trade routes as far away as Afghanistan to produce the most expensive inks. Each scribe or illuminator involved in the production of a book was required to be able to read and write in Latin and use a quill accurately.

Needless to say, this was an exceedingly time consuming and skill heavy process. It required highly specialised and trained individuals working collaboratively in institions known as scriptoria that would be able to produce these texts, including working texts for preaching in churches, portable gospel books and liturgical books for preaching “on the move” or in the local community and exegetical texts for scholars in monasteries.

Some high status books would be adorned with bindings made with precious metals covered with gemstones. The Lindisfarne Gospels’ gloss, produced by the scribe Aldfrith in the 10th century, records name of the smith who produced the beautiful (and now lost) binding for the Gospel book as Bilfrith the Anchorite:

“And Billfrith the anchorite forged the ornaments which are on it on the outside and adorned it with gold and with gems and also with gilded-over silver – pure metal.”2

It should be remembered that exquisitely decorated books such as the Lindisfarne Gospels were “the exception, not the norm”, but they demonstrate on a stunning visual plain the reverence with which the written word was held in the early medieval period.3 Ceremonial gospel books like these served as the tangible embodiment of the word of God and would likely have been carried in processions to dazzle onlookers with their beauty and craftsmanship.4

Because even the simplest books were so expensive to produce, they tended to be created mostly by monks in ecclesiastical centres, and eventually paid professionals towards the end of the Anglo-Saxon period, but even then, they were still produced in ecclesiastical settings that received (primarily) royal investment to maintain their complex operations.5 It is perhaps no surprise then, that the earliest catalogue of Cambridge University Library (in 1424, so still quite a time apart from the early medieval period) recorded just 122 books in its inventory.6 (Whilst there would have been smaller individual college libraries at this time too, it is still quite a distant number from the 8 million titles now available to order from the Library shelves today).

This meant that when readers read, they engaged, and hard, in a way notably different to how we might engage with books today, especially those of us who aren’t religious. Whilst reading aloud in a class might fill many young people and teenagers with anxiety today, reading aloud was the norm in the medieval period, and it was deemed quite uncommon to read in your head, especially in the earlier medieval period. Indeed, many texts in the early-mid Anglo-Saxon period were set out in a style known as per cola et commata, with specific punctuation designed to aid the process of reading aloud. However, the inefficient use of space on expensive parchment meant that it became a less popular practice in the later period.

Simply reading the words, though, was just one of multiple different stages of reading in the early medieval period. Followed accurately, these steps were said to reveal the will of God:

lectio - the book is held in the hands and the words are spoken aloud.

meditatio - the memorisation process; the words are seen, heard and fixed in the mind.

oratio - the process of prayer in which the reader would to gain an increased understanding of the Divine.7

In other words, understanding the literal meaning of the text was just the first step, then it must be known by heart in order to be able to contemplate it fully. The literal meaning was like a “husk” which concealed the true divine nature of the text; only once it had been understood and memorised could it be contemplated for its deeper allegorical meaning.8

This was known as the process of lectio divina (divine reading) - the idea was that, through this careful study and rumination upon the words they had taken memorised, scholars of the faith would become enlightened to God’s will. These revelations could then be implemented in one’s daily life, and only then would the learning process be truly complete.

Insights such as these, of course, required a huge amount of concentration and hard work, so, perhaps understandably, exegetical texts from notable biblical scholars (works that explain or provide commentary on biblical texts, often as a result of the lectio divina process) were incredibly popular. It is said that copies of Bede’s commentary on the Gospel of Luke were requested so frequently that the monastery at Wearmouth-Jarrow struggled to produce enough manuscripts to meet demand.

Reading was a spiritual exercise, closely linked with meditation but it was an intimate physical process too.9 Research by Prof. Kathryn Rudy of the University of St Andrews has revealed how late medieval readers kissed and rubbed personal prayer books, particularly Books of Hours, and that many readers would come back to specific texts, likely for comfort or reassurance.10 Much of this wear was revealed by the siginificant darkening of folios that were more intensely used; the more they were used, the more grime and oils would be deposited by their readers onto the pages.

Such physical devotion is not necessarily a feature of modern readers’ engagement with books, but some of these traditions have continued into the present. The Augustine Gospels, thought to be the Gospel book brought by St Augustine in 597 as part of his conversion mission to Kent, are central to the ceremony of the enthronement of the Archbishops of Canterbury, and have been venerated by Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Whilst these traditions are generally restrained to formal ceremony today, they serve as a reminder of early medieval reading habits.

(As a side note for the curious, the Augustine Gospels, along with a huge number of wonderful Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, were digitised back in 2009 by Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and made available for the general public online in 2017. You can explore the Gospels with this link.)

In the process of studying for my PhD, I know that I am perhaps guilty of skimming through texts quite fast in order to gather the necessary information required; I try to get through books relatively quickly so I can tick them off my ever growing reading list, summarise key details, flicking through indexes frantically. I remember feeling mediocre when book influencers on Instagram and TikTok would proudly reveal how many books they read in a single month or year. I had this horrible feeling I should be reading faster, to get as much information in as physically possible. What do you mean you took a month to read a single novel?

Yet as the winter approaches and the world starts to slow down a little, perhaps the reading habits of medieval monks are a good reminder to all of us to spend more time with our books with the cold evenings drawing in and really consider what we can learn from them, to savour them more. I’m currently attempting to read some more classic fiction (right now I’m reading Wuthering Heights which is feeling very atmospheric) and have decided I’m going to be trying to chew on those words a little more, instead of trying to race through it at breakneck pace.

Who knows, I might get some divine inspiration from Emily Brontë.

Thank you for reading M.R. James Appreciation Society! If you enjoyed this post, please feel free to share it with a fellow bibliophile who might be keen to learn a little about early medieval reading practice.

All posts from M.R. James Appreciation Society are free to read for all subscribers. However, if you do feel compelled to support open access history, paid subscriptions are switched on and available from £3.50 per month.

If you would like to support me monetarily but would prefer to not to commit to a monthly subscription, you can buy me the cost of a cup of tea instead! Any and all support goes directly towards my Substack writing and outreach work.

M.P. Brown. The Lindisfarne Gospels: society, spirituality and the scribe. (Toronto, 2003).

D. Rollason. Northumbria 500-1100: the creation and destruction of a kingdom. (Cambridge, 2008).

R. Gameson. “The material fabric of early British books.” in R. Gameson (ed). The Cambridge History of the Book, vol. 1. (Cambridge, 2011).

N. Netzer. “The design and decoration of Insular gospel-books and other liturgical manuscripts, c . 600 – c . 900”. in R. Gameson (ed). The Cambridge History of the Book, vol. 1. (Cambridge, 2011).

R. Gameson. “From Vindolanda to Domesday: the book in Britain from the Romans to the Normans”. in R. Gameson (ed). The Cambridge History of the Book, vol. 1. (Cambridge, 2011).

H. Higgins. The Grid Book. (Cambridge, 2009).

L. Sterponi. “Reading and meditation in the Middle Ages: Lectio divina and books of hours” Text & Talk 28–5 (2008).

L. Sterponi. “Reading and meditation in the Middle Ages: Lectio divina and books of hours” Text & Talk 28–5 (2008).

L. Sterponi. “Reading and meditation in the Middle Ages: Lectio divina and books of hours” Text & Talk 28–5 (2008).

K.M. Rudy. “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2:1-2 (2010).

Excellent, Olive.